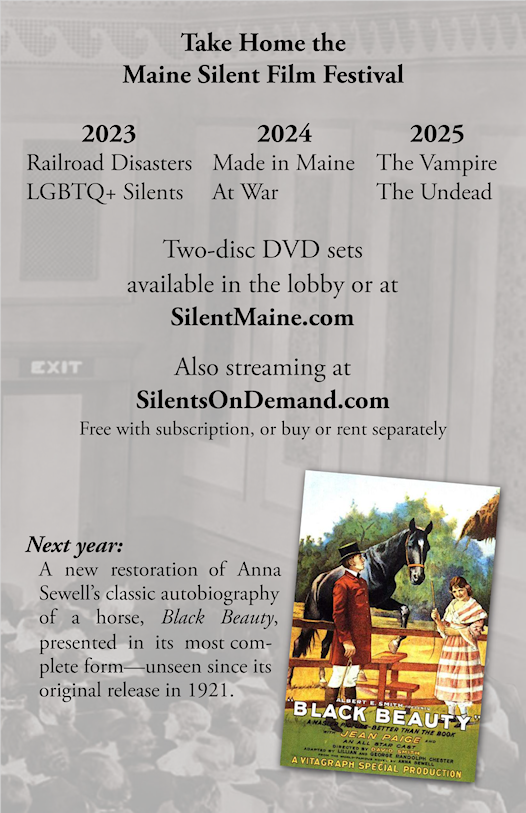

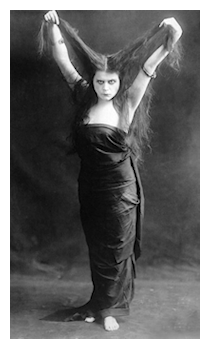

The Vampire

Theda Bara!

She was born in the wind-swept Sahara in a Bedouin tent perched against the Sphynx and in the very shadow of the pyramids.

From her mother, a French actress, she learned “the languages, expressions, and the art of pantomime” while from her father, an Italian artist, she learned “how to paint, and the beauty and combination of colors.” From the desert sands, steeped in the mysteries of countless ages, she learned the occultic practice of seduction.

Theda Bara!

Said to be the reincarnation of Cleopatra, her name is an anagram for Arab Death and she is the living embodiment of the vampire—that ruthless and uncaring femme fatale who will lead men astray, take from them all they are worth, and then discard their empty shells when they have nothing more to offer, with a long history of ruining sheiks and potentates one after another.

Or, at least, that was Theda Bara as she was introduced to the press by studio publicists from Fox Film, meeting them in a luxurious hotel suite decorated in an outrageous Egyptian fashion and kept as stiflingly hot as the Sahara itself, while Bara, in voluminous oriental silks and dripping with precious stones, stroked a leopard cub, looked mysterious, and said nothing at all.

Not one word of Theda Bara’s origin story was true. And for that matter, though happy to repeat the studio line, no reporter had believed it, nor did hardly any of the general public outside of young children and the exceptionally credulous. Fantastic origin tales were the rule and were seen as an extension of an actor’s on-screen persona. They were not expected to be factual.

Not one word of Theda Bara’s origin story was true. And for that matter, though happy to repeat the studio line, no reporter had believed it, nor did hardly any of the general public outside of young children and the exceptionally credulous. Fantastic origin tales were the rule and were seen as an extension of an actor’s on-screen persona. They were not expected to be factual.

Theodosia Goodman was born of middle-class Jewish parents in Cincinnati, Ohio—her father a fabric cutter and her mother a wigmaker. All her life she wanted to act and started doing so at an early age, exploiting every industry connection she could make and inventing impressive if wholly fictious experience to be noticed and to propel her career.

Theda Bara’s survival rate is one of the worst of any early film star. Her filmography is almost entirely lost, with nearly all her titles having burned in the 1937 Fox film vault fire. Of her features, only three still exist in complete form: A Fool There Was,

East Lynn, and The Unchastened Woman.

A Fool There Was is Theda Bara’s first leading role as well as the first film in which she is credited by that name and not as Theodosia Goodman.

The film was based on the play by Porter Emerson Browne (which in turn was based on Rudyard Kipling’s poem The Vampire, and that had been based on an illustration of the same name by his cousin, Philip Burne-Jones), and for a play released in 1909, A Fool There Was is one of the most mid-Victorian works ever staged, abounding in heavy-handed, moralistic melodrama and over-wrought, stilted dialogue. Critics and audiences alike did not fail to notice this, but it was the vampire character that caught the public’s attention and at once made Theda Bara a star.

and for a play released in 1909, A Fool There Was is one of the most mid-Victorian works ever staged, abounding in heavy-handed, moralistic melodrama and over-wrought, stilted dialogue. Critics and audiences alike did not fail to notice this, but it was the vampire character that caught the public’s attention and at once made Theda Bara a star.

In A Fool There Was, the feature film of this evening’s program, John Schuyler (Edward José) plays a respected diplomat tasked with handling a delicate situation in Europe. On the ship overseas, he meets a character known only as The Woman (Theda Bara), who has already driven one man to suicide and now has her sights on him.

Theda Bara was not the first screen vamp, nor the second or the third, but she quickly eclipsed all those who came before her. As far as filmgoers were concerned, after A Fool There Was, Theda Bara became the vamp.

But being the vamp was a double-edged sword. Bara was acutely aware that the public’s interest in vampire films would

sooner or later wane, and she did not want to be typecast to a dead-end character type.

She wanted to do romances and light dramas, and above all else, she wanted to break into comedy. In short, she thoroughly tired of vampirism, which in interviews she denounced as ludicrous. No woman, she said, was ever like a screen vamp and no man ever reacted as her make-believe victims did.

Bara was thankful for A Fool There Was propelling her to stardom but she wanted to move on. Fox, however, had little interest in trying new things when the old things were still raking in money. The few non-vampire films they did produces with Bara, though some were critically acclaimed, were not popular with audiences, and the single comedy they allowed her to make was an abysmal failure across the board.

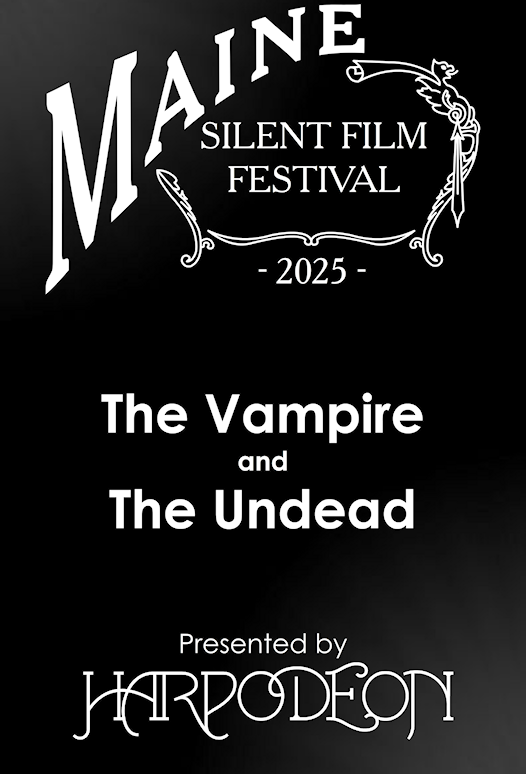

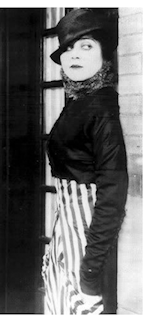

But, in the end, Theda Bara was right. The public’s fascination with vampires did subside, and it subsided quickly. From a dangerous, existential threat, the vamp became camp—a parody of itself—too silly to take seriously. As early as 1916, just a year after the release of A Fool There Was, Gloria Swanson was already lampooning vampirism in the first comedy short of this evening’s program, The Danger Girl.

As is the case for most of the short films Gloria Swanson and Bobby Vernon made for Triangle in the mid-1910s, frenetic scenes of comedic action was the goal. It was at most a secondary concern that the film had a plot that was at all coherent. In broad strokes, a “danger girl” (Helen Bray) arrives at the Beverley Hills Hotel and all the men fall under her spell. To save Bobby, Gloria disguises herself as a man in order to monopolize the vamp’s attention.

As the years went by, vampirism in drama continued to decline as did Theda Bara’s popularity. Her contract with Fox was not re-newed after filming wrapped on The Lure of Ambition in 1919. Six years later and after a lucrative but widely panned attempt to break

into Broadway, Theda Bara would play a vampire for the last time in The Unchastened Woman for Chadwick Pictures before retiring from the screen. Chadwick was a poverty row studio that produced largely cheap filler to pad out the second half of double-features. Theda Bara herself, however, was by now a wealthy woman, thanks in no small part to A Fool There Was.

into Broadway, Theda Bara would play a vampire for the last time in The Unchastened Woman for Chadwick Pictures before retiring from the screen. Chadwick was a poverty row studio that produced largely cheap filler to pad out the second half of double-features. Theda Bara herself, however, was by now a wealthy woman, thanks in no small part to A Fool There Was.

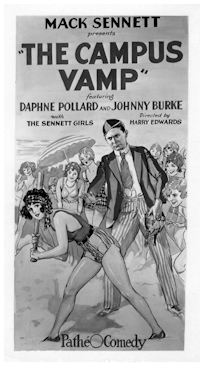

Unlike in drama, in comedy, vampires still abounded. One of the last silent vamp comedies released at the very tail end of the silent era was The Campus Vamp, a Mack Sennett production from 1928.

Set in Beverley College, the film follows a vamp’s attempt to steal away another girl’s boyfriend and the efforts that girl’s friends go through to prevent it. The Campus Vamp is noted for starring Carole Lombard as the vamp before she rose to fame and for its Technicolor beach baseball finale.

When Theda Bara died in 1955, her obituaries repeated the tale of her birth in a Bedouin tent perched against the Sphynx in the very shadow of the pyramids, only now, enough time had passed that most readers believed it.

The Undead

After yesterday’s program of vampire films, today focuses on the undead, which is to say, films about characters who have an unexpected resurrection after they are mistakenly believed to have died.

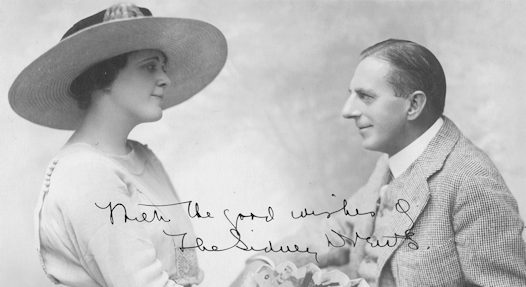

Today, “silent comedy” is almost synonymous with slapstick, but not all comedy in the silent era was physical. At Vitagraph, Larry Semon starred in rough and tumble slapstick shorts, but also at Vitagraph were John Bunny, Flora Finch, and Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Drew, who featured in shorts that were less centered on action and were more situational comedies of error.

In A Regiment of Two, the first short of the evening, Ira (Sidney Drew) and his son-in-law (Harry T. Morey) pretend to enlist in the 13th Regiment, covering their regular boys’ night out by claiming they have to go to drills. When the 13th is called to the front, the two go fishing, but on finding out that “their” regiment was completely wiped-out, they must find some way to come back to life.

A Severe Test, directed by Alice Guy-Blaché, finds a wife

(Marian Swayne) doubting her husband’s love when, after a year of marriage, he is no longer as affectionate as he was when they were newlyweds. To test his love, she pretends to commit suicide, but she confuses envelopes and the suicide note she wrote to her husband went to her friend, and the note intended for her friend letting her in on the game went to her husband, who decides to play along.

The large majority of Alice Guy-Blaché’s films are believed to be lost. This evening’s screening of A Severe Test is derived from a print in the Harpodeon film collection and is the only known copy still extant.

There are two resurrections in the final short starring Solax veterans Lee Beggs and Billy Quirk: The Egyptian Mummy. A professor has just discovered the formula for the elixir of life and wants an ancient Egyptian mummy to test it out on. Dick, trying to earn enough money to win the professor’s approval and marry his daughter, sells him an alcoholic vagrant (Joel Day) he has bribed to lie still in a papier-mâché sarcophagus. The plan goes perfectly until the “mummy” starts drying out and getting antsy.

The evening concludes with the theatrical premiere of Harpodeon’s 2025 restoration of Playing Dead, a rare feature-length drama from usual comedy duo Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Drew. Jimmy’s wife Jeanne falls for Proctor Maddox (Donald Hall), a socialist and feminist activist, and wants a divorce. To free Jeanne while avoiding a scandal, Jimmy stages a fake suicide instead, but he forgot to leave his will where it could be found.

The only releases of Playing Dead previously available have been sourced from very poor small-gauge film prints. The restoration screening today comes from an incomplete but exceptionally high quality original 35mm nitrate print with the missing footage filled in from the best latter-day print available.

Our Accompanist

Doug Protsik

Doug has been playing and performing the “Old Time Piano” style since the early 1970s. Developed in the latter half of the 19th century the style includes ragtime, accompanying fiddle tunes for dances, foxtrots, waltzes, and other popular dance music and songs from that era. It was the predominant style when silent movies appeared around 1910 and it became a standard job of piano players to accompany the films since there was no sound.

Doug learned the art of putting together a score appropriate for silent movies from Danny Patt, who first played for the silent movies when he was growing up in Union, Maine in the 1920s. Danny’s talent for this music was reestablished in the 1980s as a growing interest in viewing old silent movies became of interest to the public once again. Since Danny passed away in 1999, Doug has been continuing this tradition of accompaniment, and has scored and performed for countless showings throughout Maine and internationally. This work led to his composing original authentic scores for silent movie restorations for Turner Classic Movies, including titles such as Hitchcock’s The Lodger and Easy Virtue.

Traditional mood themes from composers such as M.L. Lake, J.S Zamecnik, and Erno Rapée and popular themes of the era are used to create a unique score for each movie in an original and authentic way. Doug also has established a fun aspect to the performances by including “musical jokes” in his scores, challenging the audience to recognize them. All the music is memorized, arranged, and improvised by Doug to allow for a seamless flow from scene to scene. Attending a performance allows for a wonderful musical, as well as an historic and entertaining film experience.